Learn More: Vinegar Tom

Background

- Writing in the Women's Liberation Movement

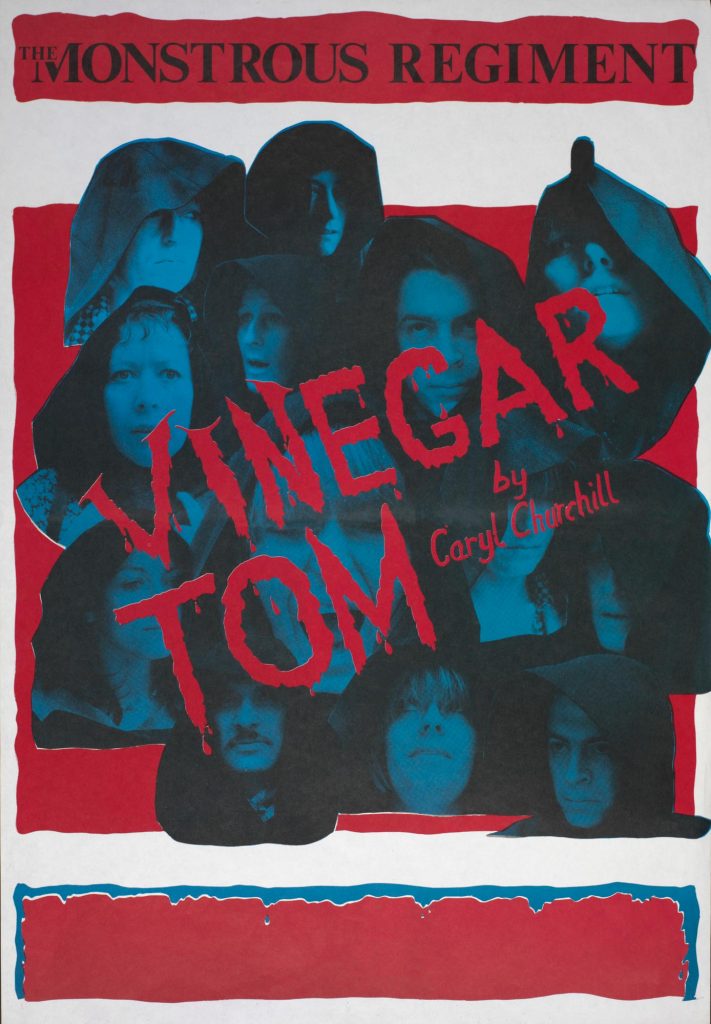

In 1976, Caryl Churchill met actors Chris Bowler and Gillian Hanna at an abortion march. Bowler and Hanna had just founded a London socialist-feminist theater company called Monstrous Regiment, who, like Churchill, “were thinking they would like to do a play about witches.” They promptly commissioned Vinegar Tom.

Poster for the original production of Vinegar Tom designed by Chris Montag. Source: Monsrous Regiment/V&A Museum. At this point in her life and career, Churchill was both a fledgling playwright and a fledgling feminist, coming into her own as a political artist a few years before she found widespread success with Cloud Nine and Top Girls.

Churchill worked in solitude for much of the 1970s. Most of her output until Vinegar Tom was radio plays she wrote at home while raising her children. Chris Bowler of the Monstrous Regiment, who originated the role of Ellen, said Churchill described her writing career and politicization before Vinegar Tom as solitary: “She felt that being at home she missed out on things we were involved in.”

Vinegar Tom marks her first time writing for a specific company of actors, as well as Monstrous Regiment’s first time working directly with a playwright. In her author’s note, Churchill writes “I felt briefly shy and daunted, wondering if I would be acceptable, then happy and stimulated by the discovery of shared ideas and the enormous energy and feeling of possibilities in the still new company.”

Churchill wrote the first draft of Vinegar Tom in three days and gave it to Monstrous Regiment, then spent the next few months writing Light Shining in Buckinghamshire with Joint Stock Theatre Company. (Joint Stock would go on to premiere Cloud Nine.) When she returned to Vinegar Tom, she created the character Betty to be played by a new member of Monstrous Regiment and wrote the rest of the songs.

The Monstrous Regiment note in the back of our scripts says “The writer/group collaboration was so close, with Caryl attending all rehearsals, it isn’t easy to pinpoint where specific ideas came from.” This play was born from a sense of ensemble in a performance context and from the need to build and connect to a collective women’s history.

Source: British Library At this point in the 1970s, feminist struggle centered on reproductive rights—women’s bodies as battleground. Britain passed its Abortion Act in 1967. On our side of the pond, Title IX became federal law in 1972, with Roe v. Wade decided the next year. In the UK, feminists organized under the Women’s Liberation Movement. Gender discrimination cases filtered through the courts, but as recent history shows, none of these freedoms are guaranteed.

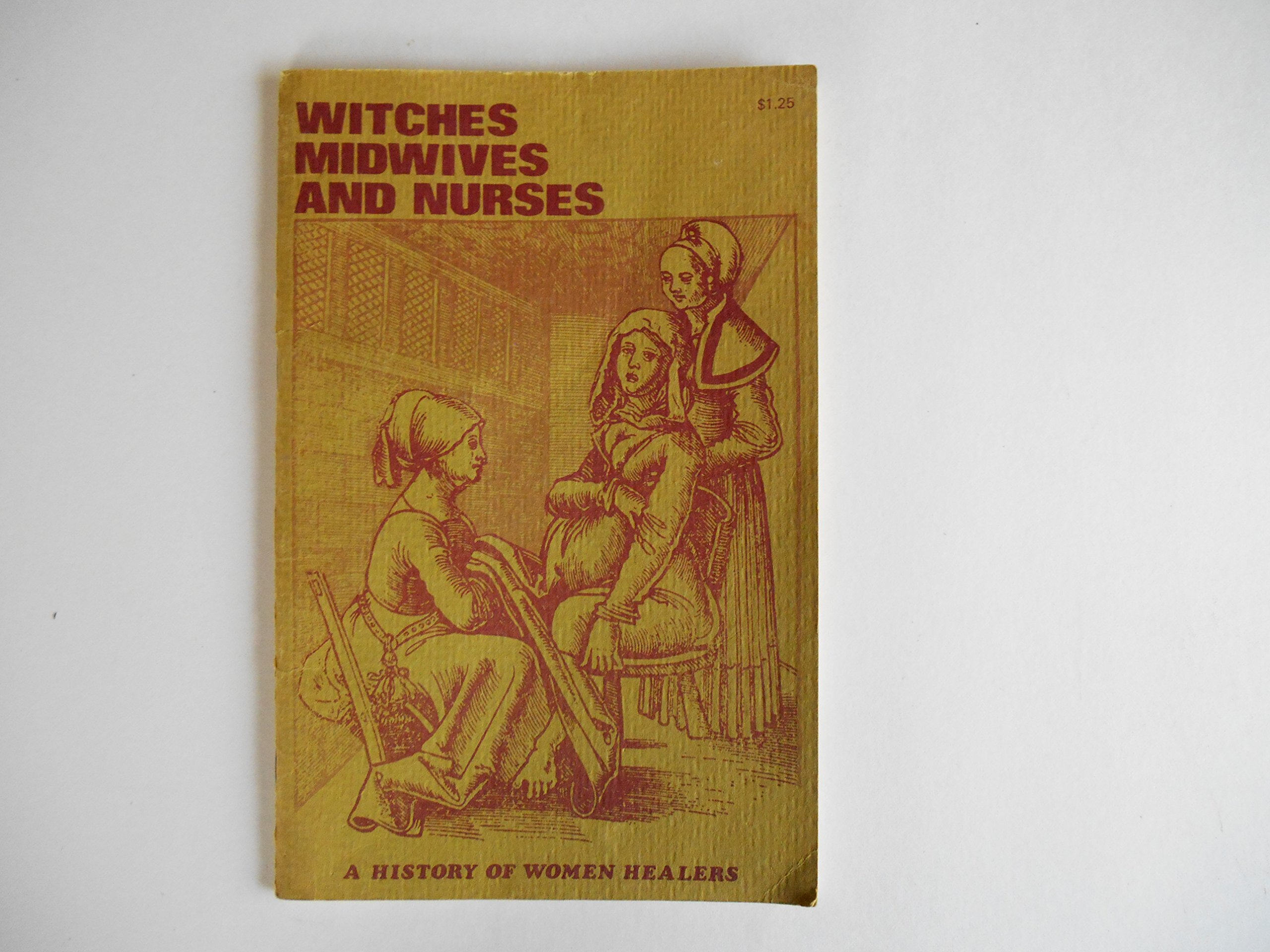

Churchill was inspired in part by a 1973 feminist pamphlet called Witches, Midwives and Nurses: A History of Women Healers. Printed by the Feminist Press at CUNY, its introduction delcares “Medicine is part of our heritage as women, our history, our birthright,” the introduction declares. Barriers between women and their medical needs are unnatural, the pamphlet claims, due to the active takeover of health care by men, from generations of wise women, midwives and, as seen in Vinegar Tom, “cunningwomen” who serve the rural poor.

Churchill was inspired by this 1973 feminist pamphlet. Source: unknown. The characters Ellen and the briefly-seen Doctor — played by seniors Nicole Labun and Ryane Lampe — exemplify the uneven access to medicine described in Witches, Midwives and Nurses. She offers treatment free of charge to the poor women at the center of the play, while only Betty’s landowning father can afford a professional, male doctor.

- Caryl Churchill

Caryl Churchill (b. Sept. 3, 1938) is a British socialist-feminist playwright. Her first plays were produced by student groups when she was at Oxford, from which she graduated in 1960. She married a year later and spent the next decade writing radio plays while raising three sons at home — an experience she called "politicizing." Her first professional stage production was Owners at the Royal Court Theatre Upstairs in London in 1972. Royal Court would go on to produce many of her plays including Cloud Nine and Top Girls.

Churchill is regarded as one of Britain’s most influential playwrights, whose work varies widely in subject matter and style but is nearly always political or feminist in nature. A recent profile for her 80th birthday aptly called her “the David Bowie of theatre.”

Caryl Churchill - Monstrous Regiment

Monstrous Regiment was formed in 1975 by a collective of female British actors frustrated with the roles available to women, which “trivialized the female experience.” Its founders were Chris Bowler, Linda Broughton, Helen Glavin, Gillian Hanna and Mary McCusker, all of whom appeared in the first production of Vinegar Tom.

They set out to create political theater that centered women, starting with a production of Scum by Chris Bond and Claire Luckham, a play set in the Paris Commune of 1870. Vinegar Tom was their second production and their first commission. They produced a total of 30 shows before becoming dormant in 1993.

As of fall 2018, there was very little information available about Monstrous Regiment online or in print. The Victoria & Albert Museum and members of Monstrous Regiment launched the company’s digitized archive this January.

Read More:

Members of Monstrous Regiment c. 1975. Source: Monstrous Regiment/V&A Museum.

- Brechtian technique, feminist criticism

Historicization and Feminist Reclamation

You might already know a bit about Bertolt Brecht’s theory of alienation in performance, or Verfremdungseffekt. Brecht, an influential German playwright, director and theorist, was last seen at IU Theatre with The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui.

The go-to example is audience interaction — breaking the fourth wall, removing the audience from complete narrative immersion. The songs in Vinegar Tom are effective in this and, as Gillian Hanna (the original Alice) admits, a little ham-handed.

“We didn’t want to allow the audience to get off the hook by regarding it a period piece, a piece of very interesting history. Now a lot of people felt their intelligence was affronted by that. They said: ‘I don’t know why these people have to punctuate what they are saying by these modern songs. We’re perfectly to able to draw conclusions about the world about the world today from historical parallels.’ Actually, I don’t believe that and, in any case, we can’t run that risk. For every single intelligent man who can draw parallels, there are dozens who don’t. It’s not that they can’t. It’s that they won’t.”

Brecht described theater as “historicizing” its performed material, which is thought of as a form of distancing effect. He wrote that an audience member shouldn’t identify too closely with a character, that the closest they can come to empathy is recognizing “If I had lived under those same circumstances...” There’s a buffer of history, the difference between our present and the onstage past that allows for a critical attitude toward society. Brecht proposed that if we stage present-day plays with the same distance, as if they’re historical, we can dissect the circumstances that shape our own social impulses and biases.

In Brecht’s idea of historicization, history is a tool for analysis and not much more. A criticism of distancing effect is that it’s cold and unfeeling, bordering antisocial. For his purposes, say in The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui, emotion was a fascist manipulation that clouded critical thought.

Churchill and Monstrous Regiment held history in a different way.

Feminist-socialist historian Sheila Rowbotham said feminism of the 1970s “has made many of us ask different questions of our past.” This is evident in both Churchill’s historical plays and Monstrous Regiment’s impulse to stage political theater about women in history.

Vinegar Tom can be read as a feminist intervention on a history written by men. “Unfortunately, the witch herself—poor and illiterate—did not leave us her story,” Barbara Ehrenreich and English wrote in Witches, Midwives and Nurses. “It was recorded, like all history, by the educated elite, so that today we know the witch only through the eyes of her persecutors.”

A feminist interest in given (male) history is distinct from Brecht’s historicization in that Vinegar Tom excavates centuries of oppression. The influential Feminist Criticism and Social Change calls the rewriting of women’s history as “not as an assortment of facts in a linear arrangement, not as a static tale of unrelieved oppression of women or of their unalleviated triumphs, but as a process of transformation.”

History

- The "Malleus Maleficarum"

Witch Trials in early modern Europe

The period of mass hysteria that saw an estimated tens of thousands of women executed by the state and mob justice throughout Europe is sometimes called “the witch craze,” from Hexenwwahm, coined by a 19th century German historian. Ehrenreich and English favor this name in Witches, Midwives and Nurses and put the body count in the millions.

Witches had been burnt and hunted since the Middle Ages, but the prevalence of witch hunting in the early modern period (c. 1500-1800) is alarming in retrospect. This was an era containing the Renaissance, the Scientific Revolution, the Age of Enlightenment and general expansion (colonialism), but also the Catholic Church at its most corrupt along with the Protestant and English Reformations.

Secular science and religious fundamentalism didn’t coexist — they were nearly segregated by region and country. “There’s some in London say there’s no sin,” Man says in Scene One, an exotic prospect to Alice, who’s spent her life in the same rural, remote, religiously homogeneous village.

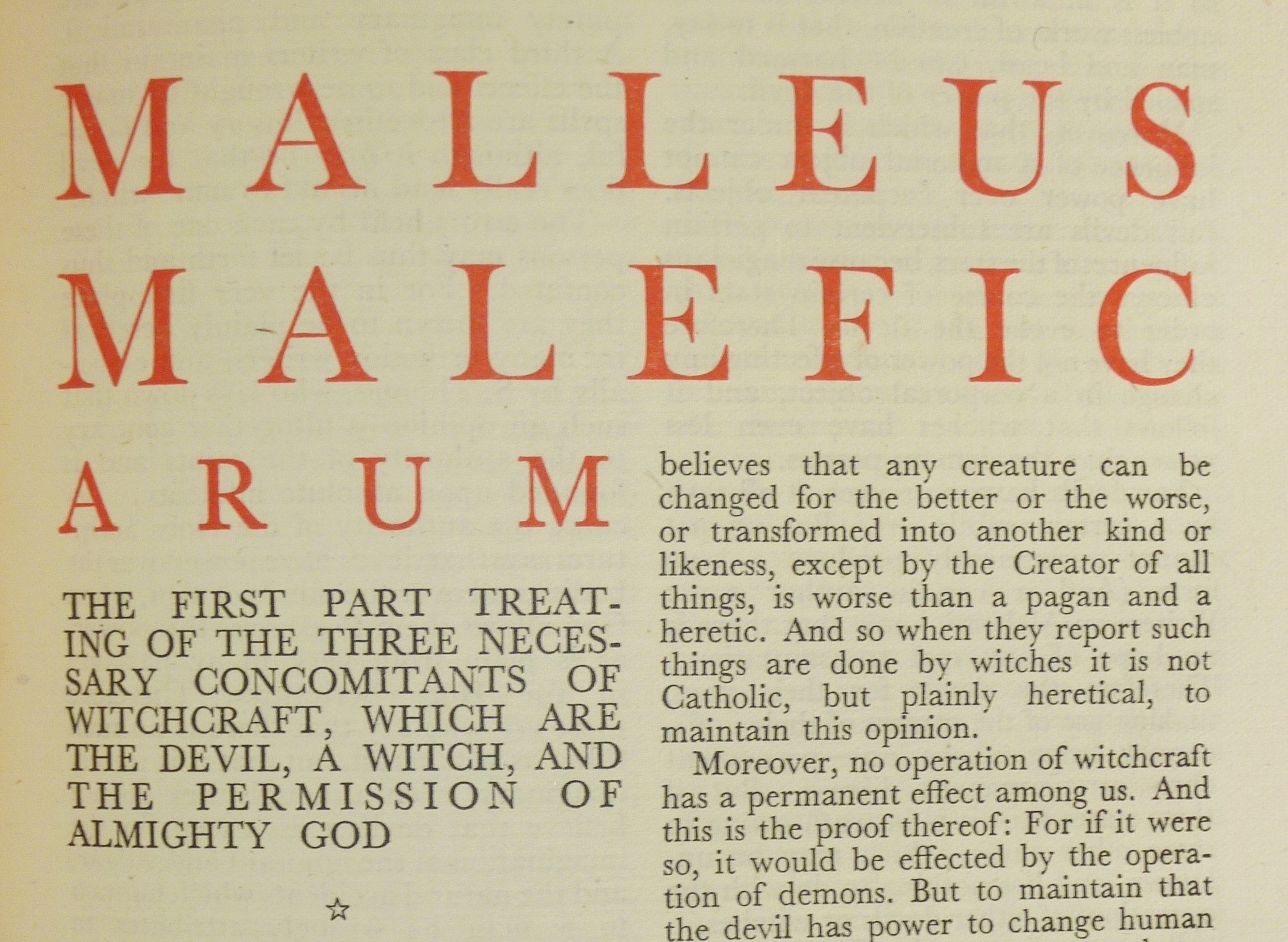

The Holy Roman Empire, comprising Germany, Austria, Switzerland and other countries in central and northern Europe, executed upwards of 20,000 witches alone from 1450-1750. It’s no coincidence that Malleus Maleficarum authors Jacob Sprenger and Heinrich Kramer were Austrian and German, respectively.

The Malleus Maleficarum is closely quoted in Vinegar Tom.

The Catholic Church in the Middle Ages and Renaissance was a powerful political body, a nation state in all but name with enormous influence over all of Christian Europe before the Protestant Reformation. The Church formally condemned witchcraft in 1140, declaring it heresy in 1258 and launching inquisitions with license to torture accused heretics.

A few centuries later, an overzealous inquisitor named Heinrich Kramer and a personal favorite of Pope Innocent VIII convinced the pope to sign a decree condemning witchcraft (even more, somehow) in 1484. It also threatened state officials with excommunication if they failed to cooperate with the Church’s inquisitors.

It didn’t work out in his favor, so he channeled his rage into the Malleus Maleficarum (‘Hammer of Witches’), published in 1487. The Church quickly condemned what was essentially a genocidal document, saying it was contrary to both Catholic doctrine and its inquisitorial ethics. It was secular courts that used the Malleus Maleficarum to identify, prosecute and murder witches. While this one document and Kramer were censured, the Church was still okay with witch trials.

As for Jacob Sprenger, some historians question the extent of his co-authorship. Like Kramer, he was a Dominican friar and inquisitor working in Central Europe who wasn’t known to write much or be as theatrical as Kramer, but these arguments don’t hold much water.

The Malleus Maleficarum is available online, but it’s both a dense and deeply misogynistic read. One section (called a ‘question’) asks and answers “Why is it that Women are chiefly addicted to Evil superstitions?” and says: “When a woman thinks alone, she thinks evil.” The book generally blames women and their sexuality for men’s sinfulness.

- Read the Malleus Maleficarum

- Click here to see an Italian fresco of witches surrounding a phallus tree, c. 1265. Witch hunting documents claimed witches would steal men's phalli and keep them as pets or put them up in trees, as one character claims in Vinegar Tom. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

- Witch trials in 17th century England

Witch Trials in 17th century England

Churchill’s primary historical reference was Witchcraft in Tudor and Stuart England by Alan Macfarlane, a regional study of witch trials in Essex. County Essex, just northeast of London, kept particularly detailed records of its witch-hunts, which Churchill credits with showing her “how petty and everyday the witches’ offences were.”

As Vinegar Tom is set in the 17th century (c. 1650), the political context of England at the time is crucial. Henry VIII’s founding of the Church of England in 1534 was the start of nearly two centuries of religious turmoil, as rule of England switched between Catholic, Anglican and Puritan leaders. The extent to which each regime persecuted witchcraft differed, but as Goody Haskins, played by junior Eleanor Sobzyck, says in Vinegar Tom, “England is too soft with its witches.” As a state, England wasn’t nearly as bloodthirsty as Scotland or the Holy Roman Empire, and Henry VIII’s children Elizabeth I and Edward VI relaxed laws against witchcraft.

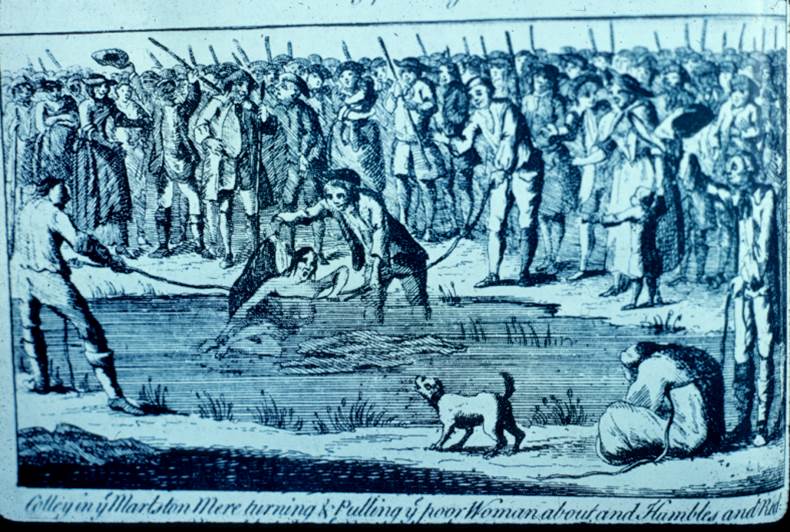

The swimming of accused witch Ruth osborne at Tring, Hertfordshire in 1751. Source: Routeledge. Elizabeth I’s successor James VI and I brought Scotland’s more rigorous witch hunting methods to England, including the water test described in Vinegar Tom. He was the author of his own treatise against witchcraft called the Daemonologie in which he claimed a witch is impervious to water due to its use in baptism.

“Swimming” a witch entailed binding the hands and feet of the accused and drowning them. If they floated, they were guilty; if they sank, they were innocent. It’s a blatantly nonsensical test that authorities in Salem, Massachusetts specifically condemned and refused to practice in 1692.

The carnage shown in Vinegar Tom didn’t begin until the English Civil War.

Spanning most of the 1640s through 1651, the English Civil War saw conflict between Parliamentarians against the monarchy and Royalists who believed in the divine rights of kings. It would end with a decade of Puritan rule, initially under Oliver Cromwell. But during Civil War, rural England was similar to the Wild West – which allowed witch hunts and hysteria to thrive.

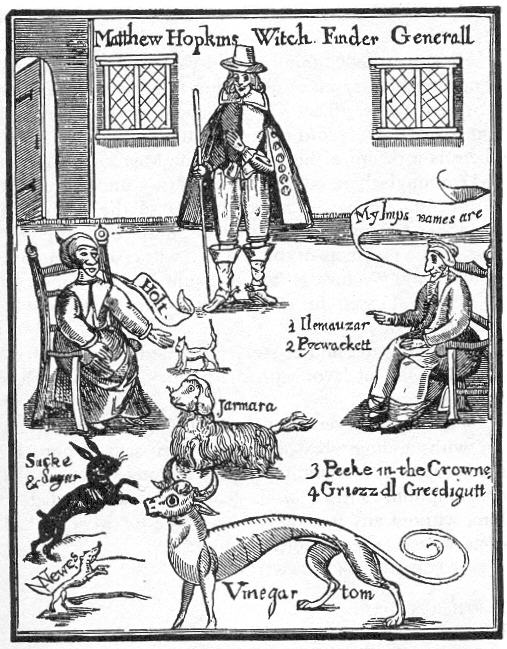

The bulk of the Essex trials Churchill referenced took place in 1645, when the self-declared Witchfinder General Matthew Hopkins and partner John Stearne prosecuted a documented 36 witches. The title “Witchfinder General” is Hopkins’ invention — he was an ordinary man who loved doing citizen’s arrests. Hopkins is believed to be responsible for as many as 300 executions in East England in his three-year witch-hunting career, all contained in the political turmoil of the English Civil War.

Hopkins is implicitly the basis for the character Henry Packer, played by Ryan Lampe. The title Vinegar Tom comes from the name of a witch’s familiar Hopkins claims to have seen in his pamphlet The Discovery of Witches. Hopkins’ Vinegar Tom is illustrated as greyhound-ox hybrid, either hideous or delightful, depending on your taste. If Hopkins saw any creature at all, he was likely an ordinary cat.

The engraving from which Churchill named Vinegar Tom. Source: Project Gutenberg

The College of Arts

The College of Arts